Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) is a voice disorder characterised by excessive tension of intrinsic and extrinsic musculature of the larynx resulting in an imbalance in normal tension that causes an improper position of the larynx leading to difficulty in swallowing, breathing and phonation.

Aspiration pneumonia occurs as a consequence of abnormal entry of exogenous or endogenous secretions into the lower airways. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia include vomiting, oesophageal disorders, difficulty in swallowing, reduced consciousness and neurological disorders. We present a rare case of MTD presenting with recurrent aspiration pneumonia with a positive bed side swallow test for dysphagia.

We conclude that in patients suffering from recurrent aspiration pneumonias, a bed side swallow test should always be performed and in patients having swallowing difficulty without neurological cause, an ear nose and throat consultation to diagnose muscle tension dysphonia or throat hypersensitivity should be taken.

Introduction

The larynx has three main functions; airway protection, respiration and phonation. Laryngeal disorders can thus affect all of these functions with varying severity.1

In normal phonation, airflow during expiration sets the small intrinsic muscles of the larynx like arytenoid, cricoarytenoids, thyroarytenoid and cricothyroid into vibration and their contraction and relaxation leads to movement of vocal folds resulting in voice production. Large extrinsic muscles such as suprahyoids and infrahyoids maintain stability of the larynx.

Muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) is a voice disorder characterised by excessive tension of intrinsic and extrinsic musculature of the larynx resulting in an imbalance in normal tension that causes an improper position leading to difficulty in swallowing, breathing and phonation.2,3,4

In some individuals the larynx can adopt a dysfunctional state that results in refractory cough, inducible laryngeal obstruction, MTD and globus pharyngeus. As these disorders appear to display significant overlap in clinical symptomatology and have features of sensory dysfunctions, they are often described as laryngeal hypersensitivity.5

Case report

A 96-year-old Caucasian male with a past medical history of osteoarthritis, falls (for which he had declined a referral to the falls clinic), pressure sores, benign prostatic hyperplasia, eczema and muscle tension dysphonia (diagnosed by ear nose and throat department), presented with vomiting and shortness of breath.

He lived alone in his house and had community support from district nurses for the care of his pressure areas. He walked with a kitchen trolley inside his house. His family was supporting him with his activities of daily living. In the hospital, on initial examination he had a pulse rate of 110/min, respiratory rate of 25/min, blood pressure (BP) of 115/92mmHg and required 35% venture mask to maintain oxygen saturation of 99%. Chest examination revealed bilateral crepitation, left more than right side. Central nervous system (CNS) examination was unremarkable.

Initial blood test results showed white cell count of 15.4 × 109/L, haemoglobin of 153g/L, platelet count of 232 × 109/L, c-reactive protein (CRP) of 14mg/L, sodium of 134mmol/L, potassium of 4.3mmol/L, urea of 5.1mmol/L, creatinine of 60µmol/L, alanine-aminotransferase of 12U/L, bilirubin of 13µmol/L and international normalized ration (INR) of 1.0.

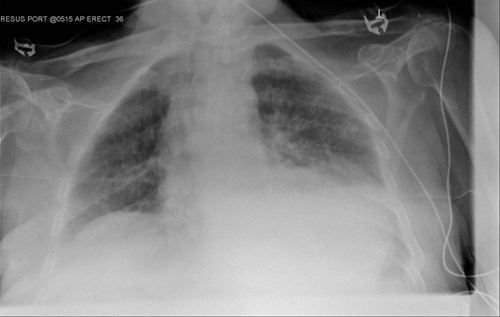

Arterial blood gas analysis showed type 1 respiratory failure. A chest X ray (CXR) revealed left lower zone consolidation and possible small left sided pleural effusion in keeping with infection (Image 1).

Since admission to the hospital, the patient had been receiving intravenous fluids and antibiotics as per the local microbiology department guidelines, including levofloxacin and metronidazole for a diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia.

Due to muscle tension dysphonia, the patient was already under the speech and language therapy (SALT) team and their review was requested. They advised nasogastric tube (NGT) feeding after giving a trial of liquid to assess swallowing to which he started dropping oxygen saturations and displayed moderate dysphagia and unsafe swallowing mechanism.

He was also seen by dieticians for an assessment of his nutrition needs and they worked closely with the SALT team.

For distressing cough and airway related secretions he also received input from the ward based chest physiotherapists. Later on, an NGT was passed under fluoroscopic guidance but was not found to be safe for feeding due to a malposition, and technical difficulty. After discussion with the patient and his family a plan of feeding at risk was made. In light of his frailty a decision was made to manage his medical problems only on the ward without any escalation to the intensive care unit.

Upon further assessments by SALT his swallowing mechanism continued to be unsafe, and during the course of his illness, the patient developed worsening of respiratory symptoms with haemodynamic instability and compromise. A repeat CXR performed eight days later showed features of increasing consolidation in the left mid/lower zone and a left-sided pleural effusion (Image 2).

His antibiotic regime was escalated to meropenem in addition to ongoing supportive medical treatment, but due to the continuing clinical deterioration he subsequently died due to sepsis induced multi-organ failure.

Discussion

Aspiration pneumonia occurs as a consequence of abnormal entry of exogenous or endogenous secretions into the lower airways. Usually there are two requirements to produce aspiration pneumonia:

- A compromise in normal defensive mechanisms that protect the lower airways, which include cough reflex, glottis closure and other clearing mechanisms

- Either a toxic inoculum coming in direct contact with lower airways, or stimulation of an inflammatory process from bacterial infection, or obstruction caused by un-cleared fluid.6

By convention, a true aspiration pneumonia is usually caused by less virulent bacteria, primarily anaerobes, which constitute normal flora in a susceptible host. Risk factors for aspiration pneumonia includes vomiting, witnessed aspiration, oesophageal disorders, difficulty in swallowing, reduced consciousness and neurological disorders.7

Poor dental hygiene, which can cause high concentration of microbes in the inoculum is also associated with increased risk of aspiration pneumonia. Aged persons, particularly ones requiring care in long term care facilities with comorbidities, are more vulnerable to develop aspiration pneumonia with one study showing that 10% patients with community acquired pneumonia had aspirated compared with 30% of those with continuing care facility (CCF) acquired pneumonia.8,9 In a study that included 134 patients with mean age of 84 years, 55% had oropharyngeal dysphagia based on water swallow test.10

Aspiration can either be silent or history of coughing while eating or drinking may indicate it. Difficulty in swallowing can easily be confirmed by bedside swallowing test using fluids of various consistencies and volume.

Sometimes pulse oximetry following a 10ml fluid challenge is also used as a simple and safe bedside test for assessing need of fluid restriction in patients who de-saturate after this test. More sensitive tests to formally assess difficulty in swallowing include video fluoroscopic swallow studies and endoscopic evaluations.11,12,13

A number of interventions including positioning, dietary changes, oral hygiene, tube feeling and drugs have been proposed in older adults to prevent aspiration.14,15

Bacteria that normally reside in upper airways or stomach are the most common cause of aspiration pneumonia. Historically, aspiration pneumonia was thought to be caused by less virulent bacteria, primarily oral anaerobes and streptococci but more recent studies have disputed this concept and have emphasised the role of more common and virulent bacteria such as staphylococcus aureus, pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other aerobic or facultative gram negative bacilli as a cause of aspiration pneumonia.16,17

Clinical features of aspirations pneumonia includes: indolent symptoms, predisposing factors like dysphagia, negative sputum cultures, absence of rigors, sputum which has a putrid odour, chest radiographs or computed tomography (CT) showing pulmonary necrosis, lung abscess or empyema.18

Treatment of aspiration pneumonia caused by bacterial infection comprise mainly of antibiotics. Pneumonia following aspiration prior to hospitalisation or in patients hospitalised for less than 48 hours require antibiotics according to community acquired pneumonia guidelines with addition of intravenous metronidazole 500mg three times a day except where co-amoxiclav is indicated, in which case addition of metronidazole is not indicated.

Pneumonia following aspiration in patients hospitalised for more than 48 hours requires antibiotics according to hospital acquired pneumonia guidelines with addition of intravenous metronidazole 500mg three times a day except where co-amoxiclav is indicated, in which case addition of metronidazole is not indicated. The duration is arbitrary and usually antibiotics are given for seven days unless cases are complicated by abscess, empyema or cavitation.

Patients are initially treated with parenteral antibiotics and if are improving clinically, hemodynamically stable, have a normal functioning gastro-intestinal tract and able to take orally can be switched to oral antibiotics. An appropriate choice in that case would be amoxicillin-clavulanate and in case of penicillin allergy; clindamycin.19

In our patient, neurological causes of unsafe swallowing were excluded and the unsafe swallowing was attributed to muscle tension dysphonia and throat hypersensitivity.

Interestingly, a study had concluded that up to 50% of patients with MTD reported dysphagia. The study also concluded that patients with MTD reporting dysphagia had higher voice and breathing impairment as compared with patients with MTD reporting dysphonia only. 20

A case report further supported that spasmodic dysphonia was accompanied by dysphagia, dyspnoea and video fluoroscopic swallowing test (VFSS) was recommended as a diagnostic test.21

Conclusion

In patients suffering from recurrent aspiration pneumonias, a bed side swallow test should be performed.

In patients having swallowing difficulty without a neurological or oesophageal cause an ear nose and throat consultation should be arranged to facilitate a diagnosis of muscle tension dysphonia.

Patients found to be at high risk of aspiration pneumonia should be managed in a multispecialty team involving speech and language therapists, and dieticians.

Besides having a good knowledge of pathogenesis and medical management of aspiration pneumonias it is vital to follow local microbiology department antibiotic guidelines for a patient centred prescription and administration of antibiotics.

Awais Abbasi, Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Good Hope Hospital (UHB NHS Foundation Trust), Rectory Road, Sutton Coldfield

Kanwaljit Singh, Department of Healthcare for Older People, Good Hope Hospital (UHB NHS Foundation Trust), Rectory Road, Sutton Coldfield

References

- Roy N, Bless DM, Heisey D. Personality and voice disorders: a multitrait-multidisorder analysis. J Voice. 2000;14:521-548.

- Dietrich M, Verdolini Abbott K. Vocal function in introverts and extraverts during a psychological stress reactivity protocol. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012;55:973–987.

- Helou LB, Wang W, Ashmore RC, et al. Intrinsic laryngeal muscle activity in response to autonomic nervous system activation. Laryngoscope. 2013;11:2756–2765.

- Groher ME, Crary MA. Dysphagia: Clinical Management in Adults and Children. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2016.

- Famokunwa B, Walsted ES, Hull JH. Assessing laryngeal function and hypersensitivity. Pulm Pharmcol Ther. 2019;56:108-115.

- Mandell LA, Niederman MS. Aspiration Pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:651.

- Taylor JK, Fleming GB, Singanayagam A, et al. Risk factors for aspiration in community-acquired pneumonia: analysis of a hospitalized UK cohort. Am J Med 2013; 126:995.

- Makhnevich A, Feldhamer KH, Kast CL, Sinvani L. Aspiration Pneumonia in Older Adults. J Hosp Med 2019; 14:429.

- Reza Shariatzadeh M, Huang JQ, Marrie TJ. Differences in the features of aspiration pneumonia according to site of acquisition: community or continuing care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54:296.

- Cabre M, Serra-Prat M, Palomera E, et al. Prevalence and prognostic implications of dysphagia in elderly patients with pneumonia. Age and Ageing 2010; 39:39.

- Smith Hammond C. Cough and aspiration of food and liquids due to oral pharyngeal Dysphagia. Lung 2008; 186 Suppl 1:S35.

- Ryu AJ, Navin PJ, Hu X, et al. Clinico-radiologic Features of Lung Disease Associated With Aspiration Identified on Lung Biopsy. Chest 2019; 156:1160.

- Osawa A, Maeshima S, Tanahashi N. Water-swallowing test: screening for aspiration in stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 35:276.

- Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:665.

- Juthani-Mehta M, Van Ness PH, McGloin J, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent intervention protocol for pneumonia prevention among nursing home elders. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:849.

- Bartlett JG. How important are anaerobic bacteria in aspiration pneumonia: when should they be treated and what is optimal therapy. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2013; 27:149.

- Polverino E, Dambrava P, Cillóniz C, et al. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia: a 10 year single-centre experience. Thorax 2010; 65:354.

- Bartlett JG. Anaerobic bacterial infections of the lung and pleural space. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16 Suppl 4:S248.

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2019; 200:e45.

- McGarey PO Jr, Barone NA, Freeman M, Daniero JJ. Comorbid Dysphagia and Dyspnea in Muscle Tension Dysphonia: A Global Laryngeal Musculoskeletal Problem. OTO Open. 2018;2(3):2473974X18795671. Published 2018 Aug 24. doi:10.1177/2473974X18795671

- Yeo HG, Lee SJ, Hyun JK, Kim TU. Diagnosis of spasmodic dysphonia manifested by swallowing difficulty in videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015;39(2):313-317. doi:10.5535/arm.2015.39.2.313