Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

At least 95 per cent of people with diabetes in the UK have type 2 diabetes. It has long been associated with maturity, corpulence, inactivity and ageing, and more recently an excess prevalence has been observed in some ethnic groups. In 1993, a survey suggested a diabetes prevalence of 3.1 per cent in people >15 years old, which more than doubled (6.5 per cent) in those >75 years.1

A report covering the period 1991-2001 noted a >50 per cent increase in prevalence of type 2 diabetes over that decade.2 Although the proportion of older people in the population increased during that time, so too had the prevalence of excess adiposity – a well recognised risk factor for type 2 diabetes. The ‘obesity epidemic’ has no regard for age, and type 2 diabetes is now being diagnosed in younger population groups, including children.3 To reduce the onset and severity of diabetes-related complications, it is important to rapidly achieve and maintain good glycaemic control and to treat other conditions that increase vascular risk.4

The nGMS contract

The value of good diabetes management has been recognised by the new General Medical Services (nGMS) contract allocating the condition nearly one-fifth of the total clinical points available within the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF).5,6 Achieving these points is based mainly on attaining specific targets for glycaemic control, parameters for increased vascular risk such as blood pressure and monitoring of microvascular disease.6 The provision of evidence-based treatment targets by learned societies has become increasingly common as guides for the provision of optimal treatment. The nGMS QOF targets use the carrot and stick principle to encourage appropriate investigations, monitoring and delivery of treatment. Whether care provision has been improved by the nGMS contract is debatable, but comparing 2004/5 with 2005/6 the total QOF points achieved have risen from >90 per cent to >95 per cent across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland with concomitant increases in points achieved for diabetes (>93 per cent to ~98 per cent) and associated vascular risk areas.7

Why have glycaemic targets?

The aim of treatment is to achieve glycaemic control that is as near to normal as possible as this reduces the incidence, progression and severity of complications. Indeed, the value of intensive intervention has been highlighted by the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), which has shown that over 12 years a one per cent decrease in HbA1c substantially reduces morbidity and mortality.8

The cost effectiveness of obtaining and sustaining optimal glycaemic control should not be underestimated, especially when considering that at least 25 per cent of patients have vascular complications at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes,9 The insidious onset of type 2 diabetes mitigates against early detection, thus people may have degenerating glucose control – impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), type 2 diabetes – for a decade prior to diagnosis in which time vascular damage has occurred.9

The clustering of cardiovascular risk factors (including glucose intolerance) that constitute the metabolic syndrome should create an index of suspicion for the presence of co-morbidities in people being treated for at least one of the risk factors. For example, in a primary care setting screening for type 2 diabetes among older hypertensive and ischaemic heart disease (IHD) patients without diabetes revealed two per cent and 2.5 per cent respectively with type 2 diabetes and a further 18.5 per cent and 12.4 per cent respectively had IGT and/or IFG10. Identification and treatment of patients early in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes greatly improves their prognosis.

It is well recognised that diabetic mortality and morbidity – both microvascular and macrovascular – continuously decrease with progression to normoglycaemia. The Joint British Societies’ (JBS2) guidelines has recommended an HbA1c ‰¤6.5 per cent while the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has opted for a less demanding HbA1c of 6.5-7.5 per cent11,12. However, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) consensus document states the goal for treatment should be as near to normal (HbA1c <6.1 per cent) as possible.)13

The QOF clinical indicator DM20 sets an HbA1c of >7.5 per cent and recommends individual patient targets should be set at 6.5-7.5 per cent, but QOF recognises that reaching tighter levels of control is diffi cult and has also set a less stringent target (DM7) of >10 per cent to encourage and reward efforts to ‘achieve the impossible’.6 However, some patients will not achieve QOF targets and exception reporting prevents a practice being penalised for factors outside its control (eg, adverse response to statins, informed opt-out).

Glycaemic control

Type 2 diabetes is a progressive disease characterised by insulin resistance and deteriorating B cell function. The conventional approach to treatment is based on lifestyle modification (eat less, move more) onto which is added oral antidiabetic drugs that target different lesions of the condition and when adequate insulin secretion can no longer be sustained, insulin therapy is introduced (Table 1). The ADA-EASD consensus document recommends initiating treatment with metformin in addition to lifestyle modification and moving to the next treatment strategy if an HbA1c of ‹13. At diagnosis an HbA1c 10 per cent is indicative of hyperglycaemia that is unlikely to be lowered to the target range using monotherapy. Provided the individual does not have late-onset type 1 diabetes, early use of combination therapy may achieve an adequate fall in HbA1c.4,13

Combination therapy for type 2 diabetes

When monotherapy ceases to maintain adequate glycaemic control the use of two antidiabetic agents with different modes of action can produce complementary and additive benefits that will improve glycaemic control and other aspects of cardiovascular risk.14-16

The addition of a second agent typically reduces HbA1c by a further 0.6-1.5 per by a further 0.6-1.5 per 1c cent14. When adding another oral agent it is important to consider the time period you would expect to achieve maximal effect. For example, sulphonylureas show a rapid effect evident on the first day of therapy with the near-maximal effect of a single dose being achieved in two weeks15.

Meglitinides target postprandial hyperglycaemia, have a faster onset and shorter duration of action, exhibiting near maximal efficacy by one week. In contrast, the thiazolidinediones (rosiglitazone and pioglitazone) act via PPARg (peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma) and therefore have a more slowly generated glucose lowering effect and may take from six weeks to three months to exert maximal efficacy in people who respond to this treatment (up to 30 per cent of patients may be non-responders).15-17

If combination therapy with two differently acting agents does not achieve glycaemic control, triple therapy may be helpful14,15,16. The most common triple combination is metformin plus a sulphonylurea plus a thiazolidinedione. It is important that triple therapy is not used in lieu of insulin therapy, which is necessary if there is rising hyperglycaemia on two agents, possibly accompanied by unintentional weight loss, polyuria and complications.

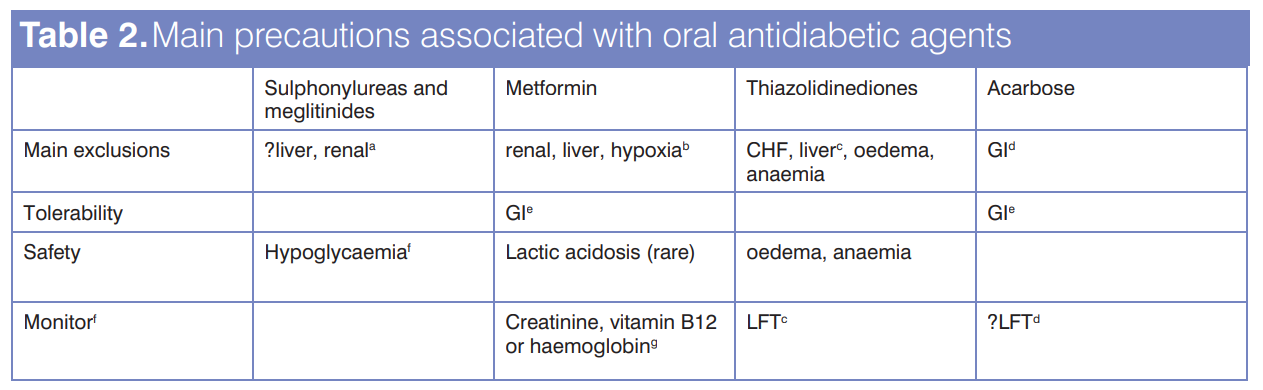

When commencing combination therapy, as when starting monotherapy, consider the appropriateness of the agent, the presence of contraindications and possible adverse events associated with the added drug. Main precautions associated with oral antidiabetic agents are shown in Table 2. When introducing a drug to achieve optimal glycaemic control, it is recommended the agent be titrated to maximal efficacy/tolerated dose to reduce the risk of adverse events such as hypoglycaemia. Titration strategies for monotherapy and combination therapy are carefully documented in Bailey and Feher15. An advantage of combination therapy is that glycaemic control may be achieved with lower doses of both agents than with either as monotherapy, thereby reducing the potential for side effects of either agent.

Responding to recommendations

Most people with type 2 diabetes will also be receiving a statin, possibly low-dose aspirin and antihypertensives – to reduce vascular risk – and older people are likely to receive treatment for other chronic conditions as well as therapies for intercurrent illness. The increasing pill burden raises the issue of compliance. Among patients prescribed a free combination of metformin and a sulphonylurea only 13 per cent showed adequate concordance, and only about one-third of patients on metformin or sulphonylurea monotherapy were taking adequate medication14,19,20. This highlights the importance of building a positive therapeutic alliance so both patient and physician are ‘singing from the same hymn sheet’19.

Simple dosing

Patients on a once-daily sulphonylurea regimen showed greater adherence compared with those on >2 doses per day,20 highlighting the value of simple dosing strategies. Several preparations are suited to once-daily dosing; for example, metformin SR which can be useful for overcoming metformin-associated gastrointestinal discomfort. Once daily administration of the sulphonylureas gliclazide MR or glimepiride produced a mean HbA1c of >7.5 per cent within nine weeks and by 27 weeks about 50 per cent of patients achieved an HbA1c <7 percent. 21 Hypoglycaemia is a recognised risk in the battle to optimise glycaemic control and it is the main side effect of sulphonylurea therapy. Use of sulphonylureas in the elderly is therefore a caution since they are more likely to live alone and have less regular meal habits. In this study significantly fewer patients on gliclazide MR (3.7 per cent) than glimepiride (8.9 per cent) noted hypoglycaemic symptoms and no third party assistance was required21; a further study using gliclazide MR over two years also exhibited a good safety profile, notably in the elderly and in patients with impaired renal function22.

2.4.1. therapy

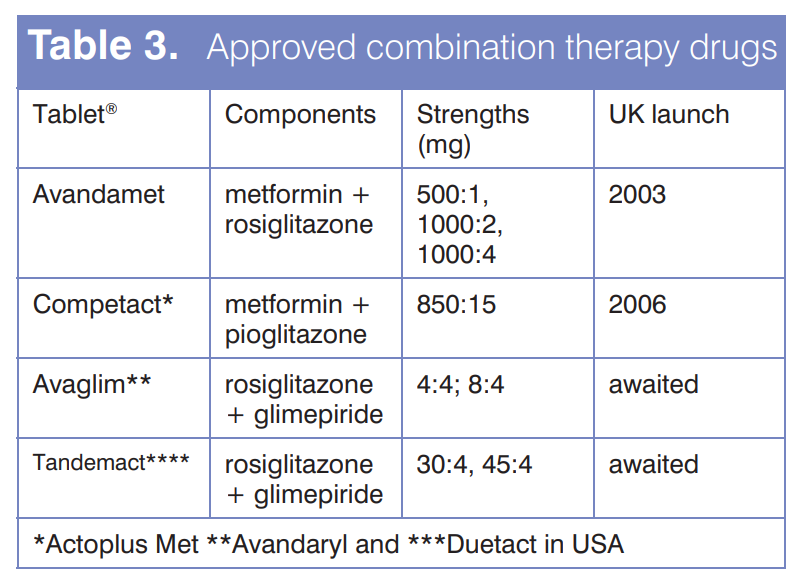

Fixed-dose combination tablets offer the convenience of two differently acting agents in a single tablet, thereby reducing the pill burden.14 The cautions attached to each of the component medications need to be considered when moving from monotherapy to 2.4.1 combination treatment. Only four such preparations have received regulatory approval for UK marketing (Table 3).

Insulin therapy

Insulin resistance is an underlying feature of type 2 diabetes initially compensated by unsustainable hyperinsulinaemia. Eventually the B-cells lose the ability to respond adequately to oral agents and insulin replacement therapy is necessary to achieve glycaemic control. The range of insulins, insulin injection devices and the advent of inhaled insulin have made insulin therapy less daunting and provides an opportunity to more closely mimic physiological insulin secretion.15,17,23 Hypoglycaemia is the main side effect associated with insulin therapy and this potential may compromise – but should not preclude – its use in the elderly, particularly those living alone. Patient education is critical to the success of insulin therapy and it is recommended that family/carers are similarly informed.15,18

The selection of an appropriate insulin regimen is an important issue which often warrants consultation with a specialist, particularly in the care of the elderly amongst whom treatment is more likely to be complicated by the presence of co-morbidities such as renal and hepatic impairment15,17. It is generally recommended that insulin therapy is initiated with a low dose (eg, 10-12 units/day) in association with regular glucose monitoring to avoid hypoglycaemia. The dose is gradually up-titrated by 2-4 units/day to achieve target control. If HbA1c is <eight per cent it is is <eight per cent it is advisable to start on a lower dose of six units/day.

Insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes necessitates higher insulin dosages compared to people with type 1 diabetes. In some patients insulin therapy is added to ongoing oral treatments – for example, insulin to a sulphonylurea regimen may reduce insulin dose and improve control while B cell function remains, or addition of metformin to insulin therapy may improve glycaemic control, reduce the weight gain and insulin dose15-17. Detailed approaches to initiating insulin therapy in primary care have been described by Hirsch et al24 and PCT guidelines can be accessed via the National Diabetes Support Team website25. Some oral agents are not licensed for use with insulin so it is important to consult the current prescribing information.

Beyond glycaemic control

Improvements in glycaemic control are associated with improvements to components of the syndrome and some classes of drugs offer additional benefits – for example, metformin and the thiazolidinediones improve aspects of rheology and some lipid parameters15. While these changes may not be statistically significant, they stack the balance in favour of the patient and assist in achieving QOF targets (e.g. DM17)6.

Excess adiposity is associated with type 2 diabetes as recognised by DM2 and production of a practice obesity (BMI ≥30) register for patients ≥16 years now warrants eight QOF points (OB1)6. Obesity is a major cause of insulin resistance and weight loss, with or without pharmacological intervention, improves glycaemic control and other metabolic syndrome conditions. Indeed, the recently introduced anti-obesity agent rimonabant appears to offer ‘greater than weight loss alone’ benefits to these parameters23.

Conclusion

The care of people with type 2 diabetes requires a holistic approach and medication strategies need to address hyperglycaemia and associated conditions of vascular risk – notably hypertension, dyslipidaemia and procoagulation – as well as the monitoring and treatment of complications. However, circumstances might warrant deviating from treating to target as part of individualising patient care.

Non-governmental guidelines, such as JBS2 and ADA-EASD consensus publications, provide targets for optimal treatment outcomes. Such targets provide a gold standard for treatment and should not be undermined by lesser targets which, though easier to achieve, do not necessarily serve the best interests of the patient.

References

- Bennett N, Dodd T, Flatley J et al. Health survey for England 1993. Social Survey Division of the Office of Population and Censuses and Surveys, HMSO, London 1995

- Fleming DM,Cross KW, Barley MA. Recent changes in the prevalence of diseases presenting for health care. British Journal of General Practice 2005; 55: 589-95

- Day C. The rising tide of type 2 diabetes. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2001; 1(1): 37-43

- Bailey CJ, Del Prato S, Eddy D et al. Earlier intervention in type 2 diabetes: the case for achieving early and sustained glycaemic control. Int J Clin Pract 2005; 59(11): 1309-16.

- Mead M. Diabetes and the new GMS contract for GPs. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2003; 3: 317-18

- Quality and outcomes framework guidance: Diabetes mellitus. February 2006.

- Kenny C. Diabetes and the Quality and Outcomes Framework:2005/06 data. Diabetes & Primary Care 2006; 8(4): 204-6

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observation study. BMJ 2000; 321: 405-12

- Bailey CJ. Early and intensive treatment: glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res 2006; 3: 145-6

- Savage G, Ewing P, Kirkwood H, Carter S. Are undiagnosed IGT/IFG and type 2 diabetes common in heart disease and hypertension? Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2003; 3: 414-16

- Managing blood glucose levels (Guideline G) September 2002. http://www.nice.org.uk/page. aspx?o=36737 (Accessed December 2006)

- JBS 2: Joint British Societies’ guidelines on prevention of cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Heart 2005; 91 suppl V,1-61

- Bailey CJ, Day C, Campbell IW. A consensus algorithm for treating hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2006; 6(4): 147-148

- Day C. Oral antidiabetic agents: Is it time to combine therapies? Diabetes & Primary Care 2006; 8(3), 124-132

- Bailey CJ, Feher MD. Therapies for diabetes. Sherborne Gibbs Ltd, Birmingham 2004. pp127

- MacIsaac RJ, Jerums G. Clinical indications for thiazolidinediones. Aust Prescr 2004; 27:7-4

- Krentz AJ, Bailey CJ. Type 2 diabetes in practice. 2nd edn Royal Society of Medicine Press Ltd, London, 2005. pp 206

- Heine RJ, Diamant M, Myanya J-C, Nathan DM. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: the end of recurrent failure? BMJ 2006; 333:1200- 4

- Emlsie-Smith A, Dowall J, Morris A. The problem of polypharmacy in type 2 diabetes. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2003; 3(1): 54-6

- Donnan PT, MacDonald TM, Morris AD. Adherence to prescribed oral hypoglycaemic medication in a population of patients with Type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabet Med 2002; 19(4); 263-4

- Schernthaner G, Grimaldi A, Di Mario U et al. GUIDE study: double-blind comparison of once-daily gliclazide MR and glimepiride in type 2 diabetic patients. Eur J Clin Invest 2004; 34: S35-42

- Drouin P, Standl E, Diamicron MR. Study Group. Gliclazide modifi ed release: results of a 2- year study in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2004; 6(6):414-21

- Day C. Glycaemic control with advanced new insulins for the treatment of diabetes. Eur Diabetes Nursing 2006; 3(3): 117-22

- Hirsch IB, Bergenstal RM, Parkin CG et al. A Real-World Approach to Insulin Therapy in Primary Care Practice. Clinical Diabetes 2005: 23:78-86

- Tameside and Glossop PCT guidelines for initiation and adjustment of insulin in type 2 diabetes in general practice, May 2005 (PDF 57KB). http:// www.diabetes.nhs.uk/ Infopoints/Insulin_Initiation.asp (accessed January 2007)

- 26. Day C, Bailey CJ. Pharmacological approaches to reduce adiposity. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis 2006; 6: 121-5