Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

The incidence of all skin cancers continues to rise and the elderly are at particular risk. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin generally affects older age groups, but both malignant melanoma and basal cell carcinoma are also commoner in the elderly than in younger age groups.

In the UK, multidisciplinary guidelines have been published on the management of each type of skin cancer and are also available online.1,2,3 NICE has issued guidance outlining the referral pathways that should occur from primary care to secondary care, as well as advice on multidisciplinary team working.4

Cancer Research UK also provides a very good up-to-date source of information on the latest trends in incidence and mortality of skin cancers.5 There are several different types of skin cancer. Some are very rare, therefore this review will concentrate on the three commonest types of skin cancer: squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and malignant melanoma (MM).

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common cancer not only in the UK but also in the rest of Europe, Australia and USA. The incidence of BCC continues to rise worldwide, however, it is difficult to find accurate figures for the incidence of BCC in the UK. Estimates suggest that official figures underestimate the true incidence of BCCs and there may be over 100,000 new cases each year in the UK.

As the population of the UK continues to age the incidence will undoubtedly continue to increase and this increase has been predicted to continue for at least up to the year 2040. Genetic factors may occasionally be important such as in Basal Cell Naevus Syndrome (Gorlin’s Syndrome) where patients may present with multiple BCCs.

Treatment options of skin cancer

There are many treatment options for the management of BCCs and the choice of these options will depend primarily on whether the patient has a low risk or a high risk tumour. Low risk tumours are those that are less than 1cm in diameter occurring on nonsensitive sites on the face and on the trunk and limbs. High risk tumours are generally regarded as those being close to the eyes and nose and which are larger in diameter or may have ill-defned edges such as the morphoeic type of tumour. Other factors which may be taken into account when deciding on the best treatment for an individual patient may include age, general health and medication (e.g. warfarin and aspirin).

Surgery

Surgical excision is regarded as the gold standard treatment for most patients with BCCs. Cure rates of over 95% are usually achieved. There is some evidence that curettage prior to excision of a primary BCC may increase cure rates. The use of Mohs micrographic surgery can increase the cure rate even further, however this is a time consuming technique and is only available in specialised centres in the UK.

Excision of a BCC is usually carried out under local anaesthetic and a peripheral margin of 4–5mm gives the best cure rate. If standard closure cannot be achieved then a more complex surgical closure using faps or skin grafs may be needed. If the BCC is incompletely excised in the vast majority of cases further surgery is indicated to ensure complete histological excision of the lesion as otherwise the recurrence rate is unacceptably high.

Curettage and cautery

Curettage and cautery is a destructive surgical technique, which may be useful for well defined low risk tumours. Five year cure rates of over 90% have been reported in carefully selected patients. Curettage is much less successful for recurrent BCCs and is best avoided in this situation.

Cryotherapy

In experienced hands, cryotherapy may be used to treat low risk and superficial lesions, and in expert hands may be used to treat high risk lesions as well.

Imiquimod

Imiquimod is a relatively new immune response modifier which is licensed for the treatment of superficial BCCs. 5% Imiquimod cream is applied to the lesion five days each week for six weeks. Significant inflammatory reactions may occur and there is direct relationship between the degree of reaction and the cure rate. Cure rates of about 80% are being reported.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT)

PDT has been used to treat superficial BCCs with cure rates of approximately 80–90%. The treatment requires the application of a photosensitiser and exposure to an activating wavelength of light about three hours following the application of the cream. This treatment usually occurs in dermatology departments and the treatment time is about 10–15 minutes. The treatment can be painful but most patients tolerate it very well. Cosmetic results are very good to excellent.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is a very effective treatment for the management of BCCs and may be particularly useful for those patients who for one reason or another cannot be treated surgically. The cure rates reported are about 90%. Long-term scarring may be a problem and if recurrence occurs then further surgery may prove difficult.

NICE and BCCs

The advice on management of BCCs has been reviewed recently and the new guidance was issued in early 2010. The advice suggests that properly trained and assessed GPs will be able to manage low risk BCCs in certain circumstances, but that high risk lesions will need to be referred to a member of the local skin cancer MDT, usually a dermatologist.4 BCCs are excluded from the current government targets for cancers.

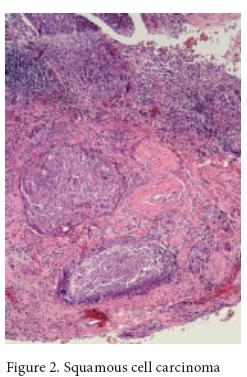

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin is a malignant tumour, which is locally invasive and also has the potential to metastasise to other organs of the body. In common with other types of skin cancer the incidence is rising. In the UK, it is the second most common skin cancer with BCC being about four times commoner. There is a fairly direct relationship between

the development of SCC and long-term sun exposure and most patients with SCC are elderly and fair skinned with a history of outdoor exposure, either through occupation or sport.

Increasingly patients who are immunosuppressed following treatment with immunosuppressive drugs for organ transplantation are seen with aggressive and multiple SCCs. Patients who have been on immunosuppression for several years are at a very high risk of developing SCC of the skin and the risk has being calculated as being between 50 and 100 times that of patients not immunosuppressed.

These patients, therefore, need to be given information at the time of their transplantation about sun avoidance and regular skin surveillance may allow early detection and treatment. Most patients with SCC have no further problems once their lesions have been removed surgically. However, there is a possibility of metastatic spread and the risk is higher in tumours arising on sun exposed skin, those with a diameter greater than 2cm, tumours greater than 4mm in depth (tumours less than 2mm in depth are very unlikely to metastasise) and those that are poorly differentiated.

Treatment

Surgery

The primary treatment of any SCC is complete removal by surgery and this is the treatment of choice for the majority of patients with SCC. There should be a minimum of 4mm of normal skin around the tumour as narrower margins are likely to leave residual tumour. Those tumours that are regarded as high risk may need wider margins of 6mm or more.

Curettage and cautery

Small, well differentiated, primary, slow-growing tumours may be removed by experienced physicians with curettage and cautery and there are some very good published results with excellent cure rates. Careful patient selection is essential and it should not be regarded as a first-line treatment for most patients.

Cryotherapy

Again for small, well differentiated tumours, cryosurgery may be an option in experienced hands, but should not be used routinely.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is an option for older patients with significant comorbidities where surgery may be difficult for a variety of reasons. The cure rate from radiotherapy is said to be over 90% in carefully selected patients.

Other treatments

Other treatments such as Imiquimod and PDT are unsuitable for treatment for patients with SCC.

NICE and SCCs

NICE recommends that all patients who may have an SCC of the skin be referred to a member of a skin cancer MDT.4

Management of primary cutaneous melanoma

Treatment![]()

The management of primary cutaneous malignant melanoma is entirely surgical. The management has changed greatly over the past 20 years; the margins of excision have become progressively narrower as a result of a better understanding of the behaviour of the disease. Initially any suspicious lesion is excised with a margin of 2-4mm to allow confirmation of the diagnosis and to plan the definitive margin of excision once the Breslow thickness is available. Incisional biopsies are not usually recommended because the biopsy taken may not be fully representative, and both diagnosis and measurement of the depth of invasion may be difficult. Incisional diagnostic biopsies can sometimes be justified when it would be difficult to excise the lesion in full, or because of the size or site of the lesion. Subsequent surgery depends on the Breslow thickness:

Intra-epidermal melanoma in situ or lentigo maligna

The aim of surgery is simply to excise the lesion in total with a clear histological margin. No further treatment is required.

Lesions less than 1mm in depth

A 1cm margin of excision is considered safe and appropriate for these lesions. Most of these can be removed with a local anaesthetic. Te wound can usually be repaired leaving a neat linear scar.

Lesions 1–2mm in depth

Most authorities recommend a margin of between 1 and 2cm for these patients, and certainly margins greater than this are not necessary.

Lesions 2–4mm in depth

Excision margins of 2–3cm are recommended for these patients.

Lesions greater than 4mm in depth

Patients with lesions greater than 4mm in depth have a poorer prognosis. It has been recognised for many years that patients in this group have a high incidence of local recurrences if the margins are too narrow. A 3cm excision margin is therefore recommended; the wound will often need to be repaired with a skin graf, but this will depend on the anatomical site.

Other treatments

Non-surgical treatments are occasionally used for lentigo maligna. These include cryotherapy, Imiquimod and radiotherapy. These treatments should only be considered in consultation with the skin cancer multidisciplinary team if surgery is not considered appropriate, or as part of a clinical trial.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

The technique of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) involves the identification and biopsy of the first-station lymph node draining an affected area. The SLN is found by injecting blue dye and/or radio-labelled colloid into the skin surrounding the primary lesion. The technique enables the identification of patients with micro-metastases affecting the regional lymph nodes and can successfully identify the sentinel node in up to 97% of cases.

Patients who are identified as having micro-metastases are then submitted to a therapeutic lymph node dissection. There is general agreement that SLNB is useful as a staging procedure in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. There are no randomised trials, however, that have shown any therapeutic benefit in patients who have undergone this technique. There may be additional potential benefits of accurate staging if adjuvant treatments, such as interferon, demonstrate proven benefit in patients with positive results.

Adjuvant treatment

Adjuvant chemotherapy (including interferon) and melanoma vaccines have so far not proved to be effective in improving overall survival in primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. A recent meta-analysis has shown that adjuvant interferon has a small effect on overall survival and a signifcant impact on relapsefree survival, however this is of uncertain clinical relevance, and as the treatment is associated with signifcant toxicity, its routine use is still controversial.

NICE and malignant melanoma

The clinical diagnosis of malignant melanoma can be very difficult, and any pigmented lesion that looks suspicious, or which has changed in the recent past, should be referred to a member of the local skin cancer MDT.4

Conclusion

Although BCCs are very rarely fatal, it is important that they are treated correctly as the risk of recurrence increases with incorrect management and any subsequent scarring, especially if on the face, may cause considerable physical and psychological upset. It is important to remember that SCCs may metastasise and so the sooner they are treated and diagnosed the better, often early treatment is straightforward and curative. All pigmented lesions that are suspicious in any way should be referred immediately for an expert opinion, and if MM is diagnosed the patient should have the benefit of management by a MDT. Correct diagnosis, early referral and expert management will at least enable early effective treatment, reduce scarring and may sometimes be life saving.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Dr Catherine Roberts, Department of Dermatology, Oxford University Hospitals, Oxford

Dr Dafydd Roberts, Singleton Hospital, Swansea. [email protected]

References

- Telfer NR, Colver GB, Morton Guidelines for the management of basal cell carcinoma. CA; Br J Dermatol 2008; 159(1): 35–48

- Motley R, Kersey P, Lawrence C; Multiprofessional guidelines for the management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Plast Surg. 2003; 56(2): 85–91

- Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L, et al. Revised U.K. guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. Br J Dermatol 2010 Jul 1. [Epub ahead of print]

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence. http://guidance. nice.org.uk/CSGSTIM [Accessed October 12 2012] 5. Cancer Research UK website. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/skin/ [Accessed October 12 2012]