Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

Learning points

- Malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia are highly prevalent in the older population.

- Good nutrition benefits cognition, wellbeing and independence as we age.

- Patients may need to change their diet as they age, particularly if they have chronic conditions.

- If malnutrition goes untreated, it costs the UK around £23.5 billion a year in health and social care costs.

- Nutrition support therefore needs to be continued post discharge, potentially for a number of months beyond a hospital episode.

A high quality, balanced diet is an integral part of healthy ageing. Good nutrition is important not just for maintaining our nutritional status and avoiding malnutrition, but also benefits cognition, wellbeing and independence as we age.

Nutrition also plays a key role in our social interactions1 and can therefore have an impact on independence, reduce isolation, and improve cognition as well.

A study by Gopinath et al (2014) explains why.2 The study looked at 1,300 patients in the US and showed that higher diet quality was associated with better quality of life and functional ability, and this was observed over a five-year follow-up period, controlling for potential confounding factors.

As a result of this study, the Academy of Nutrition Dietetics have embraced targeted intervention strategies that modify diet in the ageing population, and it is widely accepted that these interventions are needed if we are to preserve general wellbeing and physical function, and prevent deterioration and the onset of frailty.

Dr Holdoway emphasises that healthcare professionals should work together as teams and with partner agencies to provide appropriate messages for older people, and to put public health messaging into context, as patients may need to change their diet as they age, particularly if they have chronic conditions.

The prevalence, impact and relationship between malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia

Malnutrition, frailty and sarcopenia are highly prevalent in the older population, with around one in 10 older people having or at risk of malnutrition.3

While the risk of malnutrition increases on certain hospital wards, such as stroke wards, the problem is not just confined to hospitals. In fact, there are three million people malnourished or at risk of malnutrition in the UK, and 93% of those are in the community.4,5

While dieticians are uniquely placed to manage malnutrition, there are only around 11,000 registered dieticians in the UK. Waiting times can therefore be very high in the community at up to 18 weeks,6 and for this reason, Dr Holdoway urges other healthcare professionals to get involved in trying to tackle malnutrition, as dieticians can’t do it alone.

There are a number of reasons why malnutrition and frailty are so prevalent in the presence of disease and in ageing. These include:

- Disease itself may interrupt or reduce intake

- Intake may be inadequate compared to requirements (malabsorption, increased energy expenditure)

- Anorexia or loss of appetite occurs in ageing and in disease

The ability to source and prepare meals may diminish (including the motivation) - Protein requirements increase at a time intake often declines.

Sarcopenia is also a significant concern for dieticians. Characterised by a loss of muscle mass and strength, it often occurs after an injury if the patient is kept on bed rest for a significant period of time.

Patients should therefore be kept moving as much as possible while in hospital in conjunction with a good dietary intake, as preserving muscle mass is key to avoiding poor health outcomes.

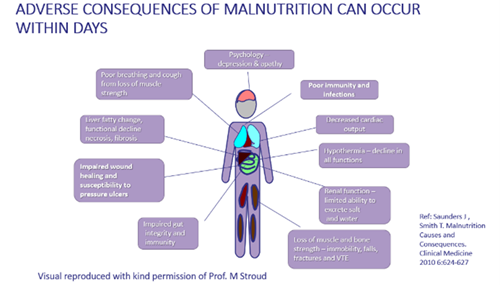

There are significant consequences of malnutrition, both to the patient as an individual and to the economy as a whole.

If malnutrition goes untreated, it costs the UK around £23.5 billion a year (Figure 1).7 These costs are not associated with nutrition supplements, which are a fraction of the overall costs, but arise due to the increased need for health and social care in patients who are malnourished.

Malnourished patients cost significantly more to care for at £7,408 while care for non-malnourished patients costs on average around £2,155.7 This difference is due to a number of reasons, including poor wound healing, increased susceptibility to infection, impaired mental and physical function, reduced activities of daily living, increased readmissions, more GP visits, and increased length of hospital stay.

Where should we focus our efforts?

While previous efforts have mainly focused on tackling malnutrition in the hospital, since 93% of malnutrition is in the community and the average hospital stay is just six days,8 this has not proven a particularly effective method.

Another issue to consider is that regardless of how nutritionally dense the food is in hospital, when patients are sick, particularly if they are suffering with a condition that affects their ability to eat and drink, they are unlikely to achieve their requirements.

Nutrition support therefore needs to be continued post discharge, potentially for a number of months beyond a hospital episode.

What can you do or encourage others to do?

Dr Holdoway suggests that wherever you’re working, if your patients are transferring from one care setting to another, you need to update and communicate your care plans and promote the role of nutritional care as they move across the settings.

She notes that that in general, patients and their families want to know about diet and nutrition. Multiple studies9,10 have shown that patients often have major concerns around their ability to eat and drink and achieve adequate nutrition to support their recovery, so it’s important professionals provide information when asked rather than be dismissive.

Understanding how to screen for malnutrition risk and complete a nutrition assessment

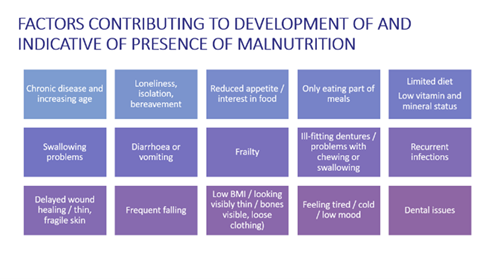

If you’re not a dietician and you’ve not been trained in nutrition, it may be more difficult to spot the signs of malnutrition than you think. Although there’s a lot of obesity in our community and in our hospital patients, they’re not protected from malnutrition. Often, when nutritional intake is poor, patients may lose muscle mass fairly rapidly in conjunction with fat mass, and therefore we should still treat them as at risk of malnutrition.

Validated screening tools are therefore very important to use in practice. The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) is very commonly used in the UK and has been promoted by NICE in both clinical guidance and quality standards for use in care settings, including in care homes and in primary care settings.

If a patient has a score of 1, because they’ve got a low body mass index or have lost some weight, then they are at moderate risk of malnutrition and may require dietary advice to prevent further deterioration.

If they’re high risk of malnutrition, they’re likely to have a score of 2 or above. For these patients, you will need to provide dietary advice with or without oral nutritional supplements and you will need to monitor them going forward.

If you don’t have access to the screening tool, incorporating conversations about nutrition during health and care assessments can be a good way to evaluate nutrition risk. For example, you could ask about the patient’s weight and height and whether they have noticed any changes recently or whether their appetite has deteriorated. You should then ask them about the factors which might be interfering with their intake (Figure 2).

Combining these questions therefore determines presence of malnutrition and facilitates the creation of an individualised care plan.

Practical based strategies for malnutrition treatment

If an assessment determines your patient is malnourished, there are a number of nutritional support solutions you can take. These are summed up by the NICE support guidance,11 which recommends:

- Feeding aids

- Texture modified diets

- Increasing the frequency of meal times (three to six meals and small snacks)

- Fortified meals and drinks

- Dietary counselling

- Oral nutritional supplements and vitamin and mineral supplements

- Tube feeding when oral intake is inadequate

- Parenteral nutrition when the gut is non or partially functioning.

If treatment is needed, it is important that the aims are determined from the beginning. Some examples of goals that clinicians might focus on are as follows:

- Improve nutritional intake

- Improved or maintain nutritional status

- Improve function (ADLs, grip strength)

- Improve clinical outcomes such as reduced complications, reduced mortality, reduced hospital readmission

- Reduce healthcare use and costs.

Oral nutrition support and dietary advice

If you have access to dieticians within your local setting, Dr Holdoway suggests you should utilise the resources that they have on hand, so they can provide you with information to give to patients and their carers.

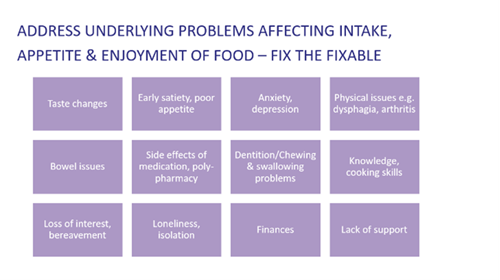

Dieticians can help you discover underlying problems affecting your patient’s nutritional intake which could be contributing to their malnutrition (Figure 3).

At this stage, it is important to ask whether a food-based approach is sufficient to replete lost stores and prevent further weight loss. If your patient has a MUST score of one or two, their deficit on a daily basis will be anywhere between 400 to 1,000 calories a day.

If it seems unlikely that a patient can get a suitable level of calories with food alone, you may want to consider using a combined approach of dietary advice along with nutritional supplements. For patients who are not on supplements, it is important they are closely monitored over a period of time to ensure they are not deteriorating.

Protein, vitamins and minerals

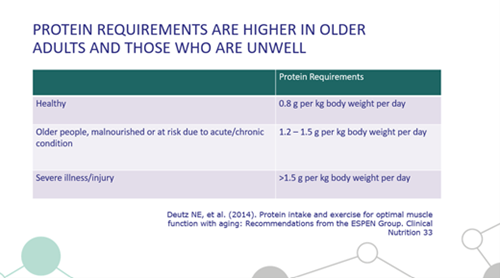

Protein requirements need to be paid particular attention to, as they are higher in older adults and those who are unwell. Older adults need 20-30g of protein at each meal time, three times a day (Figure 4).12 This is the equivalent of three eggs, 100g of steak or 80g of nut butter. If it’s unlikely your patient will keep on top of such requirements, oral supplements may be the best choice for your patient.

Fortified foods can be a great way to add extra protein, fats or sugars to food and drink, but you must ensure it does not adversely affect the taste/texture of the food as this can make your patient eat less. Specialist meal providers, like Meals on Wheels for example, often provide fortified meals so this can be a good option to consider if available in the patient’s community.

Patients will often need vitamin and mineral supplements as well to ensure they are getting adequate micronutrient intake. This is particularly true of the older population, as a high number of this group often fail to meet daily requirements of vitamins and minerals.

Dr Holdoway emphasises the importance of remembering that eating and drinking isn’t just about nutrients and therefore if your patient has eating and drinking difficulties, you should consider social and cultural factors as well as any psychological issues that might be interfering with your patient’s intake.

If a food-based approach is unlikely to go for enough, oral nutritional supplements can be a useful tool to turn to. Particularly among frail elderly who are acutely unwell and where we want to prevent irreversible loss of muscle loss and decline in function.

Supplements are particularly useful if there is a long delay for somebody to see a dietician, and health professionals can either initiate the prescription or recommend some over the counter.

When should you refer the patient to a dietician?

Dr Holdoway suggests that patients with complex conditions and those with multi-morbidities should be referred to dieticians, as they’re likely to get a number of messages about different guides that might be needed for their different conditions.

Nutrition teams should also be consulted if the patient is at high risk of malnutrition and fails to respond to first line intervention from a non-dietitian, or tube feedings or parenteral nutrition are being considered.

Suggested key actions

- Consider building screening/nutritional assessment into consultation templates, especially for those with chronic conditions such as COPD, frailty and cancer.

- Overcome barriers – work as a team, draw on each other’s strengths, collaborate and ensure resources and services for both patients and clinicians are accessible.

- Update and communicate plans as patients move across settings – engage with dietitians for complex patient management, leadership and training.

Resources

There are a whole host of supplements available; for a guide on when and how to use them please visit the malnutrition pathway website.

The malnutrition pathway website is free to use and also offers accessible patient/carer materials for optimising nutrition according to risk and top tips for GPs, pharmacists, care providers and other healthcare professionals.

To watch or download the whole presentation, please visit https://learn.pavpub.com/gm-replay-nutrition-in-the-older-patient.

Dr Anne Holdoway, Consultant Dietician and Education Officer for the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN)

Written by Lauren Nicolle, GM Journalist

References

- Gopinath et al (2014) Adherence to Dietary Guidelines Positively Affects Quality of Life and Functional Status of Older Adults, Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 114:220-229.

- Shatenstein et al (2012) Diet quality and cognition among older adults from the NuAge study, Experimental Gerontology, 47:353-360.

- Malnutrition Taskforce, accessed online (Jan 2022) at https://www.malnutritiontaskforce.org.uk/

- Elia M and Russell CA. Combating Malnutrition: Recommendations for Action. Report from the advisory group on malnutrition, led by BAPEN. 2009.

- Stratton et al. Managing malnutrition to improve lives and save money. BAPEN Report. 2018.

- Guide to NHS waiting times in England (2019) accessed online (Jan 2022) at https://www.nhs.uk/using-the-nhs/nhs-services/hospitals/guide-to-nhs-waiting-times-in-england/

- The ‘MUST’ Report. Nutrition Screening for adults: a multidisciplinary responsibility. Elia M, editor. 2003. Redditch UK, BAPEN. Elia M and NIHR (2015) Economic report; Stratton RJ, et al (2006) Br J Nutr 2006; 95(2): 325-330; Stratton et al. BAPEN Report (2018). Managing malnutrition to improve lives and save money.

- OECD (2021) Length of hospital stay (indicator) accessed online (Jan 2022) at https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/length-of-hospital-stay.htm

- Patients Association report (2011) GOV.UK research

- Holdoway A (2020) Doctoral Thesis: The role of diet in palliative care as perceived by patients, carers and healthcare professionals. University of Bath.

- NICE (2006) Clinical guideline [CG32] Nutrition support for adults: oral nutrition support, enteral tube feeding and parenteral nutrition

- Deutz NE et al (2014) Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Recommendations from the ESPEN Group. Clinical Nutrition 33