Pavilion Publishing and Media Ltd

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham, 25 Cecil Pashley Way, Shoreham-by-Sea, West Sussex, BN43 5FF, UNITED KINGDOM

A urine dipstick test cannot differentiate between a urinary tract infection (UTI) and asymptomatic bacteriuria. The usefulness of urine dipstick tests in older hospitalised patients remain to be evaluated.

The authors report an increase in the number of cases of urosepsis in local hospitals in parallel with decrease in the number of cases of UTIs in the community. This was an anecdotal observation leading to the literature search.

Objectives

To conduct a non-systematic review on the use of urine dipstick tests in hospitalised older patients.

Materials and methods

A literature search was carried out using the words, ‘diagnosis urine infections’ for articles in English from 2010 till 2020 using Pubmed, and filtered for elderly, older, clinical trial, meta-analysis, RCT, and systematic review.

Results

One randomised controlled trial (RCT) showed that antibiotic use can be lowered from 38% to 28% in care homes without any adverse outcomes.

In bacterimic UTIs, the sensitivity of urine dipstick test was 96.9%.

A review of 70 articles found that the positive predictive value of urine dipstick test was above 80%. Another review of 30 articles concluded that the urine dipstick test was useful to rule out infection.

Conclusion

There is no evidence for not doing urine dipstick tests for hospitalised older patients. The urine dipstick test has a sensitivity of 96.9% for bacterimic UTIs, and is good for ruling out a UTI if the pre-test probability is low.

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common in older people. In one cohort study the prevalence of UTIs was found to be 16.5% in community dwelling women over 65 years in the previous six months.1 In another cohort, the prevalence in one year was 30% in women over the age of 85 years.2

UTIs are defined by specific symptoms and the growth of bacteria at 105 CFU/ml on urine culture. In catheterised patients and some other exceptions, the bacterial growth at 103 CFU/ml is considered significant to make a diagnosis of UTI.

Public Health England (PHE) has produced comprehensive and precise guidance which advises that a dipstick test should be undertaken in a patient with specific symptoms on diagnosis.3

There are three issues in making a diagnosis of UTI in older patients. Firstly, patients with dementia or delirium are unable to provide a specific history of frequency, dysuria, incontinence, and pyrexia.

Secondly, older people may have asymptomatic bacteriuria, (ASB), a condition which may interfere with the diagnosis of UTI due to positive reactions for leucocytes, nitrites, and bacteria in urine. ASB is common amongst the older population. In institutionalised older people, 25-50% of women can have ASB and 15-40% of men.4 Older people may therefore be over treated, resulting in increased costs, side effects, resistance and superinfections.4

Thirdly, older patients may have atypical symptoms.

The authors experienced three cases in which the urine dipstick test was not done, and hence they were misdiagnosed. Two such cases are described below.

Case study one: acute cholecystitis

A 83-year-old woman with delirium was admitted to the elderly care ward via the emergency department with a diagnosis of urosepsis based on blood culture report revealing growth of E.Coli. A urine dipstick test was not done. The patient was treated for a presumed urosepsis. The patient was subsequently transferred to the department of elderly care.

She had a raised serum alkaline phosphatase of 211 IU/l, which led to suspicions of other causes of sepsis. An ultrasound scan of her liver revealed multiple calculi. The diagnosis was changed from urosepsis to to acute cholecystitis. The patient was then appropriately treated and transferred to the surgical department.

Case two: sepsis

A 84-year-old male was admitted with delirium. His CRP was raised at 76mg/l. The patient was treated for presumed respiratory tract infection. A urine dipstick test was not done but the culture was sent. The patient succumbed with sepsis. The urine culture report was available after the death revealing growth of Proteus.

Learning points

The authors believe that a urine dipstick test would have guided management by excluding the UTI in the second case, and would have included the diagnosis of urine infection in the first patient.

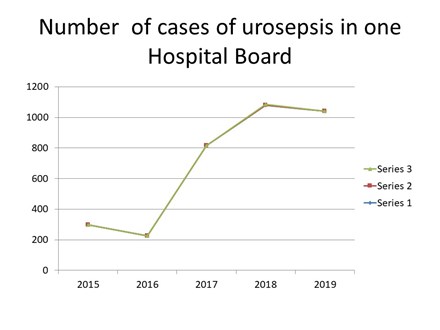

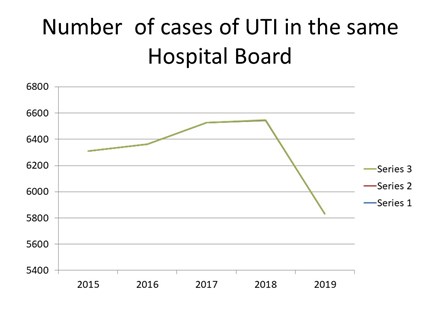

In addition, we looked at the trend of number of cases of UTI and urosepsis, at our Hospital Trust, as shown in figure 1 below.

In our Hospital Trust, the number of cases diagnosed with UTI fell from 6,550 to 5,800 over one year from 2018 to 2019. This was at a time when there was a strong drive against doing urine dipstick tests across the Hospital Trust. Simultaneously in 2019, the number of cases of urosepsis was rising from 200 per year to 1,100 per year. [Personal communication to the authors by the Hospital informatics department].

The case reports and number of cases of UTI at one Hospital Trust area, (despite the trend anecdotal), prompted us do a literature search.

Objectives

Our objective was to do a literature search and non-systematic review on the usefulness of urine dipstick tests in hospitalised older patients.

Materials and methods

We carried out a literature search using the search words, ‘diagnosis urine infections’, only for the articles in English from 2010 till 2020 using Pubmed and filtered for, elderly, clinical trial, meta-analysis, RCT, review and systematic review.

The non-systematic review was divided into two categories: articles supporting the usefulness of urine dipstick tests and articles not supporting the usefulness of urine dipstick test in older people.

We also liaised with PHE and provided the case reports and the references on the literature review.

Results and discussion

The key words ‘urine dipstick test randomised control trial’ resulted in two articles. The key words ‘diagnosis urine tract infections elderly’ revealed 474 articles.

The search with key words ‘asymptomatic bacteriuia in older elderly’ retrieved 76 results from 1981 till 2020.

Articles not supporting urine dipstick tests

Expert commentary by Froom P, et al5 after a non-systematic literature review on hospitalised older patients concluded that bacteriuria and/or pyuria cannot confirm the diagnosis of a UTI.

Spivak E, et al6 found that out of 2,225 episodes of bacteriuria, 64% were classified as having ASB, and 68% of the patients with ASB received antibiotics. It concluded that ASB was over treated with antibiotics.

Loeb et al7 carried out a cluster randomised trial on the residents of care homes in the USA and Canada. They found that antibiotic prescriptions can be brought down from 38% to 28% after multifaceted intervention targeted at healthcare professionals (education, written material, real time reminders, and outreach visits). This RCT has revealed reduction in antibiotics use without compromising outcomes such as mortality and number of hospitalisations. This study was not done on hospitalised patients.

A study by Al-makdase L, et al8 showed that education of healthcare workers reduced the number of urine dipstick tests from 77% to 25%, and cultures from 18% to 0%. This study did not reveal how they improved the diagnosis of UTI, and what was their gold standard for diagnosis. It also did not report the hard outcomes such as the mortality, morbidity, length of stay, and functional status.

Studies supporting the use of urine dipstick tests

Shimoni Z, et al9 studied 20,555 consecutive patients, out of which 228 older hospitalised patients had a bacteremic UTI. They found that the sensitivity of urine dipstick test was 96.9%.

Deville WL, et al10 carried out a meta-analysis of 70 publications. They found that the accuracy of nitrites was high in older people (Diagnostic Odds Ratio (DOR)=108). Positive predictive values were >/=80% in older patients. Accuracy of leukocyte-esterase was high in studies in urology patients (DOR=276). In addition, negative predictive values were high in both tests in all patient groups and settings, except for patients in family medicine. The combination of both test results showed an increase in sensitivity. Accuracy was high in studies of urology patients (DOR=52). Sensitivity was highest in studies carried out in patients in family medicine (90%).

St John A, et al11 in their literature search from 1966 to 2003, found 30 relevant studies that were used in a meta- analysis. Of these, 23 studies used a cut-off of 108 CFU/l. The leukocyte esterase or nitrite test combination, with one or the other test positive, showed the highest sensitivity and the lowest negative likelihood ratio. While there was significant heterogeneity between the studies, seven of the 14 demonstrated a significant decreases in pretest to post-test probability with a pooled post-test probability of 5% for the negative result.

Little P, et al12 studied various strategies of treating UTIs in general practice in female patients aged 17-70 years. Only nitrite, leucocyte esterase and blood independently predicted a diagnosis of UTI. A dipstick rule, based on having nitrite or both leucocytes and blood, was moderately sensitive (77%) and specific (70%) [positive predictive value (PPV) 81%, negative predictive value (NPV) 65%]. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves showed that for a value per day of moderately bad symptoms of over £10. The dipstick strategy is most likely to be cost-effective.

Meister L, et al 13 carried out a literature search on suspected UTIs in patients attending the emergency department, and found that urinalysis with a positive nitrite or moderate pyuria and/or bacteruria are accurate predictors of a UTI. If the pretest probability of UTI is sufficiently low, a negative urinalysis can accurately rule out the diagnosis.

Conclusion

One RCT has shown that education of healthcare professionals can reduce the use of antibiotics without compromising the outcomes of residents of care homes.

There are no RCTs to support not doing urine dipstick tests for hospitalised patients. In one health board, there was anecdotal evidence of adverse clinical outcomes and increased cases of urosepsis after stopping urine dipstick tests in hospitalised patients.

Urine dipstick tests for hospitalised older patients is useful in ruling out urinary tract infections when the pre-test probability is low.

Key points

- Usefulness of urine dipstick test in hospitalised older patients was not established before this review.

- Not doing urine dipstick test in these patients can lead to adverse outcomes.

- Urine dipstick test is good to useful to rule out the urinary infections.

Authors

- Dr Anil Mane, Consultant Care of the Elderly, Llandudno General Hospital, Llandudno; Glan Clwyd Hospital, Rhyl, Wales; Cardiff University, Wales. [email protected]

- Dr Alexander Swapna, Llandudno General Hospital, Llandudno, Wales

- Dr Tomos Lea, Llandudno General Hospital, Llandudno, Wales

- Dr Ohri Prem, Retired Consultant Physician in Elderly Care, Ysbyty Gwynedd. Bangor. Wales

The authors declare no conflict of interest. There was no funding or sponsorship for this work.

Dr Anil Mane conceptualised, reported the cases, retrieved the number of cases, did literatures search, and wrote the article. Dr Swapna Alexander carried out a literatures search and carried out a critical review of the article. Dr Lea Tomos contributed in design, literature search, and review of the article. Dr Prem Ohri carried out the literature search, set the criteria, and reviewed the article.

Author statement:

- We certify that this work is novel, and is a confirmatory review based on the references quoted at the end of the end of main article.

Declaration on funding sources:

- No specific funding was received for this work.

References

- Marques LP, Flores JT, de Barros O, Junior, et al. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of urinary tract infection in community-dwelling elderly women. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012; 16(5):436–41

- Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerstrom L, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs) in very old women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010; 50(2):132–5

- Crown copyright 2019 Public Health England. Diagnosis of urinary tract infections. Quick reference tool for primary care: for consultation and local adaptation. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/publications/urinary-tract-infection-diagnosis. Initially published on 21st of November 2007. Updated on 6th of Septermber 2019 and is based on Ref: PHE publications gateway number: GW-673

- Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria and bacterial interference. Microbiol Spectr. 2015; 3:1–25

- Froom P, Shimoni Z. The uncertainties of the diagnosis and treatment of a suspected urinary Sensitivity of the dipstick in detecting bacteremic urinary tract infections in elderly hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2017; 12(10): e0187381.

- Spivak ES, Burk M, Zhang R, et al. Management of Bacteriuria in Veterans Affairs Hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; 65(6):910-917. doi:10.1093/cid/cix474.

- Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, McGeer A, Simor A, Stevenson K, Zoutman D, Smith S, Liu X, Walter SD. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: ciuster randomised controlled trial. 2005 Sep 24; 331(7518):669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38602.586343.55. Epub 2005 Sep 8. PMID: 16150741

- L Al-makdase, P Ioannou, Z Y Tew, M Khan, M Debnath, I Ogunrinde, L Shields. Improving Diagnosis and Management of Urinary Tract Infections for Elderly Patients. Age and Ageing, Volume 49, Issue Supplement_1, February 2020, Pages i1–i8, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz183.05

- Zvi Shimoni, Vered Hermush, Joseph Glick, Paul Froom. No need for a urine culture in elderly hospitalized patients with a negative dipstick test result. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018 Aug; 37(8):1459-1464. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3271-1. Epub 2018 May 18.

- Devillé WL, Yzermans JC, van Duijn NP, Bezemer PD, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM. The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections. A meta-analysis of the accuracy. BMC Urol. 2004; 4:4. Published 2004 Jun 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-4-4

- St John A, Boyd JC, Lowes AJ, Price CP. The use of urinary dipstick tests to exclude urinary tract infection: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006; 126(3):428-436. doi:10.1309/C69RW1BT7E4QAFPV

- P Little, S Turner, K Rumsby, G Warner, M Moore, J A Lowes, H Smith, C Hawke, D Turner, G M Leydon, A Arscot, M Mullee. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Health Technol Assess 2009 Mar; 13(19):iii-iv, ix-xi, 1-73. doi: 10.3310/hta13190

- Lisa Meister, Eric J Morley, Diane Scheer, Richard Sinert. History and physical examination plus laboratory testing for the diagnosis of adult female urinary tract infection. Acad Emerg Med 2013 Jul;20(7):631-45. doi: 10.1111/acem.12171.